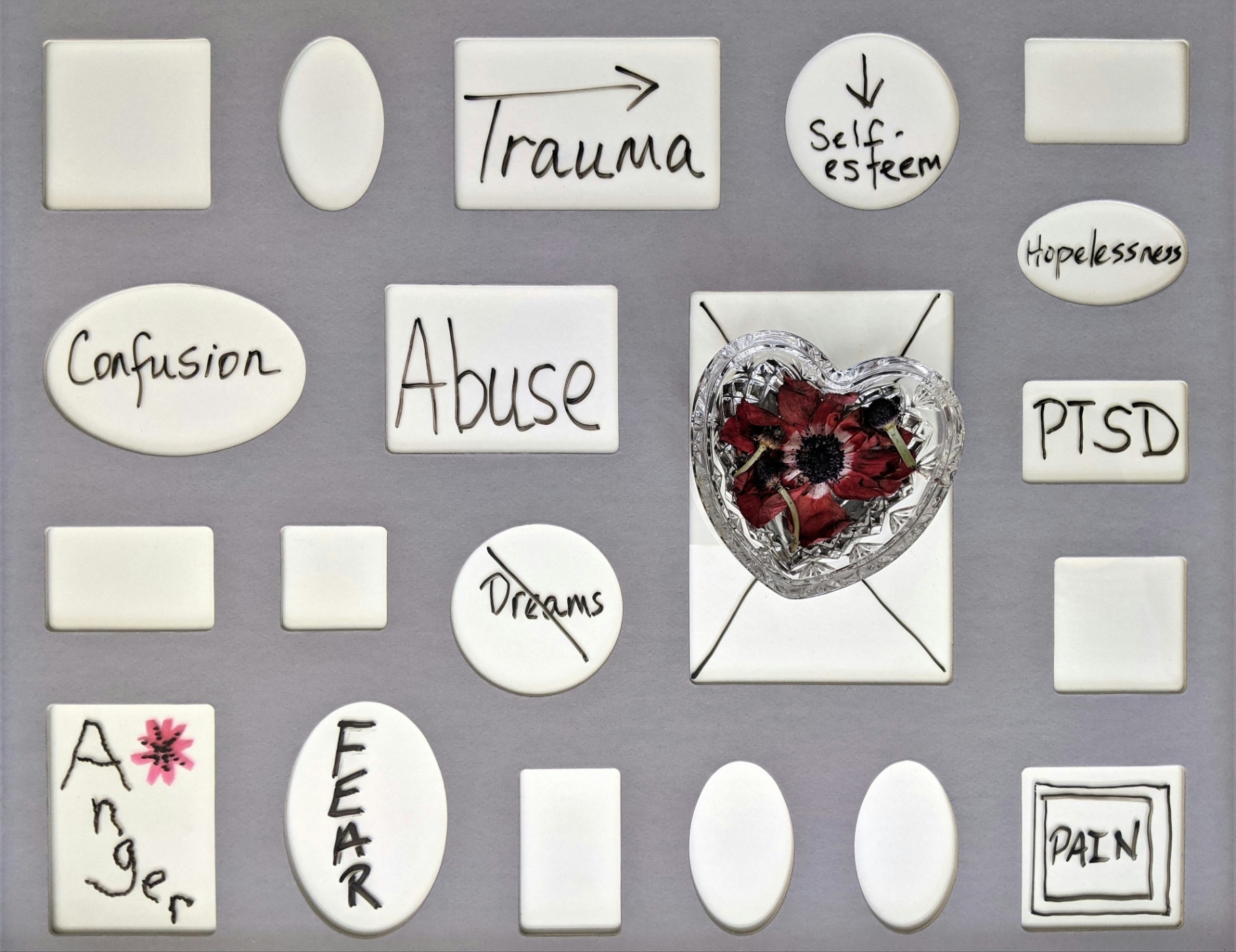

The Overlooked Aspects of PTSD: Avoidance and Disassociation

When working with clients who have experienced trauma, one of the first questions I ask is whether they have been screened for PTSD. Most of the time, the answer will be a firm “no”, usually followed by a variation on, “I don’t have flashbacks”, or “I sleep just fine”. If clients decline assessment for PTSD, we move on and focus on the symptoms that brought them to therapy, which they often self-diagnose as anxiety or depression. Those symptoms include feelings of emotional detachment, distractibility, brain fog, inability to pursue goals, and struggles to maintain or form social connections. A client may report changes in behavior that they find baffling, such as drinking more at social events, engaging in online shopping every night to “decompress”, or losing track of time when they are alone. These can all be indicators of the two most misunderstood aspects of PTSD, avoidance and disassociation.

For many of us, our understanding of PTSD comes from popular culture or from having a loved one diagnosed with the disorder. It is usually limited to just a few of the diagnostic criteria, including flashbacks or unwanted memories, insomnia, nightmares, and hypervigilance. Avoidance and disassociation are often overlooked in Hollywood portrayals of the disorder because they are harder to depict and more complicated in their expression. Even when we have first-hand experience of PTSD through a loved one, our understanding of avoidance can be limited because it is often highly internal, and we may not recognize how it is expressed through behavior. Disassociation is even more difficult to detect through outside observation. We may simply conclude that the person we love is depressed, that our partner is becoming indifferent, or that our roommate is just struggling with sleep.

Avoidance can be both internal (related to memories and feelings about the trauma) or external (related to people, places, objects, and culture that are triggering). A certain amount of avoidance in the early stages of healing can be healthy, but it can evolve into a maladaptive coping tool. Not watching the news to avoid seeing stories about an experienced natural disaster can quickly devolve into avoiding all media to prevent exposure to any natural disaster. Switching grocery stores after getting carjacked in the parking lot is an understandable choice, but this may morph into not going to any grocery store, ever. External avoidance can lead to behaviors and habits that range from mildly inconvenient to so incapacitating that they impair relationships, threaten careers, and limit social opportunities. I had an acquaintance in graduate school who was involved in a minor small airplane crash. She refused to get on a plane for years, which led to her turning down a job that required travel and missing her mother’s wedding. The people who loved her were understanding up to a point, but the avoidance quickly became a wedge in many of her relationships.

Internal avoidance is less obvious in its expression, but it can be impairing and exhausting. When I ask clients who decline to be screened for PTSD whether they have intrusive memories or thoughts about the trauma, they will often reply with some version of, “No. Because I don’t let myself”. This degree of emotional and psychological denial takes tremendous effort and can lead to maladaptive behaviors like excessive drinking, workaholism, impulsive spending, obsessive dieting, hypersomnia, or substance misuse. A brain that is preoccupied with counting calories does not have time think about the sexual assault that happened three years ago. If criticism from a coworker triggers feelings about your abusive mother, then a quick hit of online “retail therapy” may take the edge off. A rum and cola to handle the discomfort of being in a crowded public space may morph into five drinks by the end of the night. Working 12-hour days is a great reason to avoid going home to an empty apartment where you feel alone and vulnerable. Efforts at internal suppression of emotions and memories can weaken over time, causing escalation of these maladaptive behaviors. Suppression can also lead to a profound sense of emotional and physical disconnection. This is dissociation.

Disassociation in the context of PTSD refers to a distancing of self from the reality of traumatic events and the associated memories and feelings. The shock and denial stage of grief is a commonly experienced form of disassociation, especially if the death was sudden. This is a temporary state that helps us to mentally and emotionally process the loss without being overwhelmed by our grief. It is self-protective. It is not uncommon for the victims of trauma to experience a similar stage of emotional detachment during the immediate aftermath, but this temporary state can evolve to become chronic and debilitating.

Disassociation refers to two states, derealization and depersonalization. The first pertains to feelings that the world or a physical environment is not real. The second refers to feelings that the self is not real or is not experiencing what is happening. When I worked in criminal justice, a domestic violence victim described the experience of testifying at her estranged husband’s trial as, “Like watching a Law & Order.” This is a profound example of derealization. I have had clients describe intense states of depersonalization, including driving somewhere with no conscious memory of the journey or attending an important meeting without retaining any of the details. They will often minimize and dismiss these episodes, attributing them to exhaustion or “brain fog”. A friend once shared disturbing occurrences of feeling like she was leaving her body and hovering over herself while lying in bed every night. This would go on for hours and led to increasingly desperate efforts to induce sleep that escalated to mixing prescription sleeping aids with alcohol. When seeking treatment, she only discussed her difficulty falling asleep without disclosing the reason behind it, which led to a misdiagnosis of uncomplicated insomnia. When she sought treatment for alcohol abuse, she finally discussed these episodes. Thankfully, she had a very good addiction specialist who asked, “Have you ever been assessed for PTSD?”.

Written by Deanna Diamond, LPC